If you’ve ever wondered how people managed basic needs like clean water and waste disposal during Japan’s turbulent Sengoku Jidai period (1467–1603), you’re not alone. Many history enthusiasts assume advanced plumbing is a modern convenience—but what about warriors and villagers in 16th-century Japan? In this article, we’ll explore whether Japan in the Sengoku Jidai period had plumbing, how sanitation worked, and what daily life looked like without today’s infrastructure. Let’s uncover the surprising reality behind hygiene in feudal Japan.

What Was the Sengoku Jidai Period?

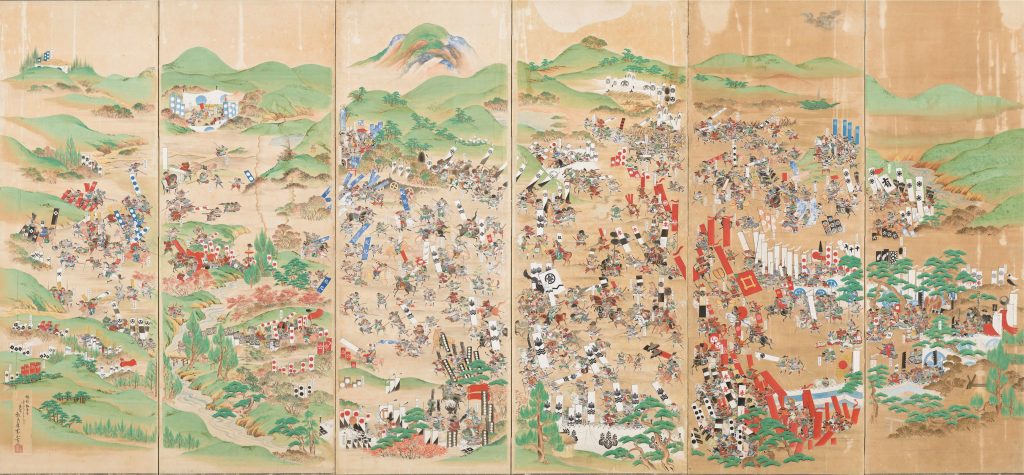

The Sengoku Jidai—or “Warring States Period”—was a time of near-constant civil war, social upheaval, and political fragmentation in Japan. From the mid-15th to early 17th century, regional warlords (daimyō) battled for control, castles rose on hilltops, and villages adapted to survive. Amid this chaos, infrastructure like roads, water supply, and sanitation systems was often rudimentary—but not nonexistent.

Understanding daily life during this era requires looking beyond battlefields. How did people access water? Where did waste go? These questions reveal how Japanese society balanced practicality, tradition, and emerging engineering—even without modern plumbing.

Did Japan in the Sengoku Jidai Have Modern Plumbing?

Short answer: No—but they had functional water and waste systems.

Modern plumbing—as we define it today (pressurized pipes, sewage networks, flush toilets)—did not exist in 16th-century Japan. However, the Japanese developed clever, low-tech solutions for water access and sanitation that were surprisingly effective for their time.

Unlike contemporary Europe, where urban waste often flowed through open streets, Japanese communities prioritized cleanliness, influenced by Shinto beliefs (which emphasize purity) and later Buddhist practices.

How Did People Access Clean Water?

Water was essential for drinking, cooking, bathing, and agriculture. In the Sengoku Jidai, people relied on several natural and engineered sources:

- Rivers and streams: Most villages were built near freshwater sources.

- Wells: Common in towns and castle grounds; dug manually to access groundwater.

- Aqueducts and bamboo pipes: Some castles and elite residences used bamboo conduits to channel water from springs or rivers into courtyards or kitchens.

- Rainwater collection: Roofs were designed to channel rain into barrels or cisterns.

For example, at Himeji Castle (constructed during the late Sengoku/early Edo period), historians have documented gravity-fed water channels made of wood and stone that supplied water to kitchens and gardens.

“Japanese water management in the pre-modern era was remarkably adaptive,” notes Dr. Susan Hanley, historian and author of Everyday Things in Premodern Japan. “They maximized natural topography to distribute water without pumps or metal pipes.”

Waste Disposal & Sanitation Practices

Without sewers, how did people manage human waste?

1. Dry Pit Latrines (Kumitori-toilet)

Most common in rural areas and lower-class homes, these were simple holes in the ground covered by a wooden seat. Waste was periodically removed and—surprisingly—used as fertilizer.

2. Night Soil Collection (Shimogoe)

In towns and near castles, human waste was collected by specialized workers and sold to farmers as high-quality fertilizer. This practice, called shimogoe, was so valuable that landlords sometimes charged tenants based on waste output.

According to records from the Edo period (which followed Sengoku), waste was so prized that theft of night soil occurred—and strict laws governed its trade. While direct Sengoku-era records are sparse, historians believe the practice began earlier, during this chaotic transitional phase.

3. Separation of Functions

Japanese homes often had separate areas for cooking, bathing, and waste. Bathing typically occurred in wooden tubs filled by hand, using water heated over fire. Bathwater was reused (e.g., for laundry) to conserve resources.

Plumbing in Castles vs. Villages

| Feature | Castles & Elite Residences | Rural Villages & Commoners |

|---|---|---|

| Water Source | Springs, aqueducts, wells | Rivers, wells, rainwater |

| Waste System | Latrines over moats or cliffs; night soil | Pit latrines; composting |

| Bathing Facilities | Wooden tubs; heated water | Shared tubs or river bathing |

| Sanitation Priority | High (for hygiene and defense) | Practical but limited |

Castles like Matsumoto and Inuyama were built on hills with natural drainage, often placing latrines over moats or steep drops—a design that doubled as defense and waste disposal. Soldiers and servants used these, while daimyō might have private chambers with better ventilation.

Influence of Religion and Culture on Cleanliness

Two cultural factors shaped sanitation:

- Shinto: Emphasizes kegare (impurity) and ritual cleansing. Washing hands and rinsing mouth before entering shrines was common—reinforcing daily hygiene.

- Buddhism: Monasteries maintained clean grounds and often had advanced water systems for rituals and gardens.

These beliefs encouraged regular washing, even without running water. Unlike medieval Europe—where bathing declined due to plague-era misconceptions—Japanese bathing culture thrived, laying groundwork for the famed sentō (public bathhouses) of the Edo period.

Comparison with Contemporary Europe

While 16th-century European cities like London or Paris struggled with open sewers and disease outbreaks (e.g., the Black Death), Japan’s decentralized, agrarian society avoided dense urban waste crises. Waste recycling and clean water access contributed to lower epidemic rates in pre-modern Japan.

However, this doesn’t mean Japan was “advanced” in plumbing—it simply prioritized different solutions based on environment, culture, and available technology.

The Legacy: From Sengoku to Edo Plumbing

The Sengoku Jidai laid the foundation for Edo-period (1603–1868) urban planning, which included:

- Municipal night soil collection systems

- Public bathhouses with wood-fired boilers

- Sophisticated waterworks in cities like Edo (Tokyo)

The famous Kanda Aqueduct, built in the early 1600s, supplied clean water to Edo’s growing population—showing how wartime innovations evolved into civic infrastructure.

For more on Japan’s historical sanitation systems, see this overview on Japanese sanitation history (Wikipedia).

FAQ Section

Q1: Did samurai have toilets in their castles?

Yes. Castles featured latrines (called setchin), often built over moats or cliffs. Higher-ranking samurai had more private and ventilated facilities.

Q2: Were there public baths during the Sengoku Jidai?

Public bathhouses (sentō) became widespread in the Edo period, but simpler communal baths existed earlier—especially near temples and in towns.

Q3: How did people wash their hands without running water?

They used dipper-and-basin sets (chōzu-bachi) near entrances. Water was poured from a ladle—still seen at Shinto shrines today.

Q4: Was human waste really used as fertilizer?

Absolutely. Known as shimogoe, it was a valuable agricultural commodity. Farmers paid for it, and it helped sustain Japan’s rice-based economy.

Q5: Did plumbing exist in any form?

Not in the modern sense—but gravity-fed channels, wells, bamboo pipes, and waste recycling formed a functional, sustainable system.

Q6: Why didn’t Japan develop sewers like Rome?

Japan’s population was less urbanized, and its terrain (mountainous, rainy) favored decentralized, nature-integrated solutions over large-scale stone sewers.

Conclusion

So, did Japan in the Sengoku Jidai period have plumbing? Not as we know it—but its people engineered practical, eco-friendly systems that met their needs with remarkable efficiency. From bamboo water pipes to night soil economies, feudal Japan proves that innovation isn’t always about technology—it’s about resourcefulness, culture, and respect for cleanliness.

If you found this dive into historical sanitation fascinating, share it with fellow history buffs on Twitter or Facebook! And don’t forget—next time you turn on a faucet, you’re benefiting from centuries of global plumbing evolution.

Stay curious. Stay clean. 💧

Leave a Reply