Designing a plumbing system for a building might seem overwhelming—especially if you’re an architect, builder, or DIY enthusiast tackling your first major project. Yet, a well-planned plumbing layout is essential for health, safety, and long-term cost savings. Whether you’re working on a single-family home or a multi-story commercial structure, understanding how to design a plumbing system for a building is a critical skill that blends engineering principles with practical know-how. In this guide, we’ll walk you through every step—clearly, confidently, and in compliance with modern standards.

Why Is Proper Plumbing Design So Important?

A faulty plumbing design can lead to leaks, water contamination, inefficient flow, and even structural damage. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), household leaks waste nearly 1 trillion gallons of water annually in the U.S. alone. Beyond waste, poor systems risk violating local building codes and failing inspections.

More importantly, plumbing impacts occupant comfort and public health. That’s why the International Plumbing Code (IPC)—adopted by most U.S. states—sets strict guidelines for pipe sizing, venting, drainage, and fixture placement.

Step 1: Understand Local Codes and Regulations

Before sketching a single pipe, review your local plumbing codes. While the IPC provides a national baseline, states and municipalities often add amendments. For example:

- California requires water-conserving fixtures under Title 24.

- New York City enforces stricter backflow prevention rules.

💡 Pro Tip: Contact your local building department or visit ICC’s website for the latest code editions. Ignoring local regulations is the #1 reason plumbing plans get rejected.

Step 2: Determine Water Demand and Fixture Units

Every plumbing fixture (sink, shower, toilet, etc.) contributes to the building’s total water demand. Engineers use Fixture Units (FUs)—a standardized measure defined by the IPC—to calculate required pipe sizes and capacity.

| Lavatory Sink | 1 | 1 |

| Shower | 2 | 2 |

| Toilet (1.6 gal flush) | 3 | 3 |

| Kitchen Sink | 2 | 2 |

| Washing Machine | 2 | 3 |

Example: A 3-bedroom home with 2 bathrooms typically requires ~20–25 WFSU. Use this total to size your main supply line—usually ¾-inch to 1-inch diameter for residential builds.

“Underestimating fixture units is a rookie mistake that leads to low water pressure and system strain,” says Maria Chen, P.E., a licensed plumbing engineer with 15+ years in MEP design.

Step 3: Plan the Layout – Supply and Drainage

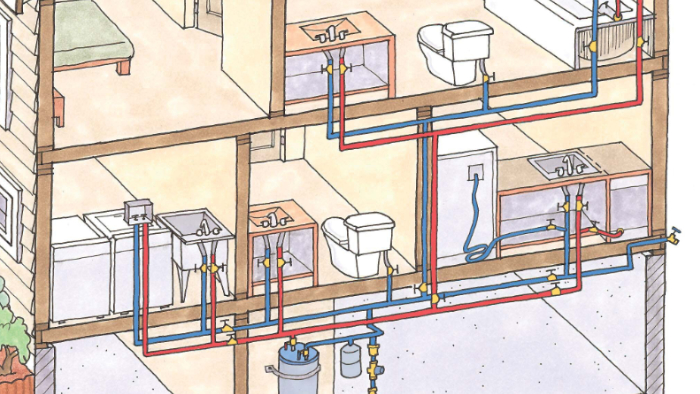

A plumbing system has two main subsystems:

- Water Supply System: Brings clean, pressurized water into the building.

- Drain-Waste-Vent (DWV) System: Removes wastewater and equalizes air pressure.

Water Supply Layout Tips:

- Use a main shutoff valve near the water meter.

- Install branch lines to each fixture with appropriate pipe material (e.g., PEX for flexibility, copper for durability).

- Maintain minimum pressure: 40–80 psi is ideal (per IPC §604.3).

DWV System Essentials:

- Slope matters: Drain pipes must slope ¼ inch per foot toward the sewer.

- Vent pipes prevent siphoning and sewer gas entry—every fixture needs venting, either directly or via wet/dry vents.

- Keep traps (e.g., P-traps under sinks) filled with water to block odors.

For deeper technical insights, refer to the plumbing system entry on Wikipedia , which outlines historical and modern standards.

Step 4: Choose the Right Materials

Material choice affects cost, longevity, and code compliance:

| PEX | Supply lines | Flexible, freeze-resistant | Not UV-resistant |

| PVC | Drain lines | Cheap, corrosion-resistant | Not for hot water |

| Copper | Hot/cold supply | Durable, recyclable | Expensive, requires soldering |

| Cast Iron | Commercial drains | Extremely quiet, long-lasting | Heavy, costly to install |

For most U.S. residential projects, PEX for supply + PVC for drainage is the go-to combo.

Step 5: Size Pipes Correctly

Undersized pipes cause pressure drops; oversized ones waste water and money. Use IPC Table E103.3(2) to match fixture units with pipe diameter.

Quick Reference (Residential Cold Water):

- 1–2 fixtures: ½-inch pipe

- 3–6 fixtures: ¾-inch pipe

- 7+ fixtures: 1-inch pipe

Always include a 20% safety margin for future additions.

Step 6: Incorporate Water Efficiency & Sustainability

Modern plumbing design prioritizes conservation:

- Install low-flow fixtures: EPA’s WaterSense-labeled toilets use ≤1.28 gpf (gallons per flush).

- Consider greywater systems (where legal) to reuse sink/shower water for irrigation.

- Insulate hot water pipes to reduce wait time and energy use—saves up to 3–4 gallons per shower.

Step 7: Create Detailed Plans and Get Permits

Your final plumbing blueprint should include:

- Pipe routing (with dimensions and slopes)

- Fixture locations

- Valve and cleanout access points

- Backflow prevention devices

Submit plans to your local authority for permit approval before breaking ground. Skipping this risks fines or demolition.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- ❌ Ignoring venting requirements

- ❌ Using incompatible pipe materials

- ❌ Poor slope on drain lines (causes clogs)

- ❌ Placing pipes in unheated areas without insulation

FAQ: How to Design a Plumbing System for a Building

Q1: Do I need an engineer to design a plumbing system?

For residential single-family homes, many states allow licensed plumbers or even knowledgeable homeowners to design systems. However, commercial or multi-family buildings almost always require a licensed professional engineer (P.E.) due to complexity and safety regulations.

Q2: How deep should plumbing pipes be under a building?

In most U.S. climates, supply lines should be below the frost line (typically 18–48 inches deep). Inside the building, pipes run within walls, floors, or ceilings—never exposed to freezing temps without insulation.

Q3: Can I reuse existing plumbing in a renovation?

Yes—but only if:

- Pipes meet current code (e.g., no lead or galvanized steel in supply lines)

- The layout supports new fixture locations

- A licensed plumber inspects and approves the system

Q4: What’s the difference between DWV and water supply pipes?

DWV (Drain-Waste-Vent) pipes carry wastewater away via gravity and are not pressurized. Water supply pipes deliver clean water under pressure. They use different materials, fittings, and installation rules.

Q5: How much does plumbing design cost?

For a 2,000 sq ft home, a professional plumbing plan costs $800–$2,500. Commercial projects range from $5,000–$20,000+, depending on scale and MEP integration.

Q6: Can I design plumbing using software?

Yes! Tools like AutoCAD MEP, Revit, or even free options like SketchUp + plugins help visualize 3D layouts, check slopes, and generate material lists.

Conclusion

Learning how to design a plumbing system for a building isn’t just about pipes and fittings—it’s about creating safe, efficient, and sustainable spaces where people live and work. By following local codes, calculating demand accurately, choosing the right materials, and planning meticulously, you’ll avoid costly mistakes and ensure long-term reliability.

If you found this guide helpful, share it with a fellow builder, architect, or DIYer on social media! And remember: when in doubt, consult a licensed plumbing engineer—your future self (and your clients) will thank you.

Stay dry, build smart. 💧🔧

Leave a Reply